Interview with our guest Postdoctoral Researcher Dr. Mariam Coulibaly from Burkina Faso

Dr. Mariam Coulibaly's inspiring career trajectory in agricultural research on indigenous crops.

Mariam Coulibaly has been a guest scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Biology Tübingen, in the Department of Molecular Biology, for 3 months. She received funding from The World Academy of Sciences (TWAS) - Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Cooperation Visits Programme (TWAS-DFG) for researchers from sub-Saharan Africa. We discussed her enthusiasm for promoting indigenous crops, such as Kersting’s groundnut or groundbean (Macrotyloma geocarpum), cultivated in West Africa. Her research focuses on the crop’s genetic improvement of the crop to develop new cultivars. She discusses her PhD thesis in Benin on exploring the species, her ongoing promotion efforts, and the advantages of collaboration in enhancing resource access.

Tell us about your research and what sparked your enthusiasm for this subject.

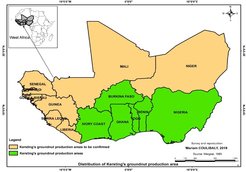

My research focuses on the neglected culture of Kersting’s groundnut (KG), Macrotyloma geocarpum, a nutrient-rich legume that I studied during my PhD thesis at the University of Abomey-Calavi in Benin. It is a semi-domesticated crop grown mainly in Burkina Faso, Benin, Ghana, Togo, and Nigeria for human consumption and animal feeding. KG seed is high in proteins and essential amino acid content. It also demonstrates agronomic benefits such as atmospheric nitrogen fixation and thus to soil fertility improvement, and provides substantial incomes to many smallholder farmers.

Initially, I knew little about this crop; I deepened my knowledge during my PhD research, thanks to the MoBreed programme, which aimed to promote and improve indigenous crops. This programme took me to Benin, where I discovered the incredible potential of these crops to contribute to sustainable food and nutritional security. I was very excited to be able to contribute to a field that has a direct impact on rural communities and to work on innovative solutions to contemporary agricultural challenges.

What challenges have you encountered in your research, and how have you overcome them?

Breeding crops, particularly indigenous species, requires navigating through various disciplines, agronomy, genetics, molecular biology, and ecology. For instance, I used the ecological modeling approach to examine Kersting’s groundnut distribution in present and future climatic scenarios. The method was new to me, so the challenge was running the statistical analysis. Hence, I have drawn on the knowledge of experts in ecological niche modeling in the USA and Benin. This collaborative approach has enabled me to fully overcome this hurdle and achieve this specific objective of my research. I immensely enjoyed learning and working with these experts.

The lack of adequate genomic resources for Kersing’s groundnut for the analysis of its genome-wide diversity and the genetic basis of key traits of interest is also a limitation to overcome. Therefore, my postdoc protocol aims to generate a reference genome for the species towards marker-assisted breeding to accelerate new cultivars’ development. This led me to spend three months in the Department of Molecular Biology at the Max Planck Institute for Biology, Tübingen, under the TWAS-DFG programme.

How would you rate the importance of international collaboration in your work?

International collaboration is essential in my field of research. It gives us access to resources, skills and perspectives that are not often available in our countries. This is the case with the TWAS-DFG scientists cooperation visits programme, which allowed me to conduct my research into sequencing the Kersting’s groundnut genome and deepen my knowledge in bioinformatics. It allowed me to work with renowned researchers such as Prof. Detlef Weigel and his group.

This type of collaboration gives opportunity to researchers to broaden their networks and, hence, work on joint projects that will benefit not only their country but other countries as well. It also opens the door for future generations of scientists in terms of capacity and career building.

What is your vision for the future of your field of research?

As a scientist, I am passionate about harnessing advances in modern technologies to fast-track the development of improved crop varieties. In the next 10-20 years from now, I expect to be a senior scientist involved in collaborative breeding programs and teaching activities in our research institutes and abroad.

As a researcher in plant breeding, I am enthusiastic to contribute to improving smallholder farmers' livelihoods by providing them with improved crops cultivars that meet their needs, hence, contibuting to food security and safety in Burkina Faso and Africa.

As a lecturer, I firmly believe that training, capacity building and access to facilities are the keys to the future of science in Africa. I will contribute to training future generations of plant breeders by giving them the tools and knowledge they need to succeed.

Furthermore, being a woman scientist, I would like to be a good role-model and mentor to upcoming females in breeding science. I expect, therefore, to have contributed to the capacity building of female scientists that are capable to make their own way through the scientific world and to impact-driven research in society.